Abstract

Background

The parathyroid-hormone-related peptide has been shown in earlier studies to be secreted by pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, although its secretion by gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors is very rare. In contrast, a number of solid tumors, such as lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma, have frequently been shown to secrete parathyroid-hormone-related peptide.

Case presentation

We describe a case report of a 53-year-old Canadian white patient with refractory parathyroid-hormone-related-peptide-mediated hypercalcemia associated with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and review the available research. Our patient had severe hypercalcemia initially refractory to treatment. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed a pancreatic lesion and multiple hepatic metastases. A liver biopsy confirmed metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor expressing parathyroid-hormone-related peptide. Circulating parathyroid-hormone-related peptide levels were at the upper limit of normal preoperatively and decreased sharply postoperatively following debulking of the tumor. Blood calcium levels eventually normalized on long-term administration of the somatostatin analog lanreotide in combination with denosumab.

Conclusions

We describe a case with parathyroid-hormone-related-peptide-mediated hypercalcemia in a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (parathyroid-hormone-related peptide tumor). Refractory hypercalcemia was likely the result of parathyroid-hormone-related peptide overproduction by the tumor and resolved following normalization of parathyroid-hormone-related peptide levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), alternatively referred to as islet cell tumors, are an uncommon form of neoplasm originating from the pancreatic endocrine tissue. On the basis of factors such as histological differentiation, grade, stage, tumor burden, somatostatin expression, and functionality, PNETs are categorized in a variety of ways [1].

Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas have a clinical incidence of 1–2 per million annually and constitute 1–2% of all pancreatic tumors; however, autopsy investigations show that their frequency is substantially higher, occurring in 0.5–1.5%, and that < 1 per 1000 induce a clinical syndrome [2].

The incidence and prevalence of these tumors appear to have increased in recent years. This is likely due to a variety of factors, including the increased awareness and recognition of these tumors, the improvement in pathological diagnosis involving immunohistochemical staining for specific neuroendocrine tumor markers, and incidental detection by imaging studies carried out for another reason [for example, abdominal ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] [3, 4].

Though they can appear at any age, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors typically arise in the fourth or fifth decade of life. There is no gender preference for these tumors, though some subtypes may show a modest preference for either gender [5]. Children and adolescents seldom experience PNETs, and in these cases, it is typically linked to a genetic or familial predisposition [6].

PNETs are typically sporadic, but they can also arise in conjunction with hereditary (familial) syndromes, including neurofibromatosis, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL), multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1), and tuberous sclerosis; PNETs can arise in roughly 30–80% of MEN-1 patients, 20% of VHL syndrome patients, 10% of neurofibromatosis patients, and 1% of tuberous sclerosis patients [2].

PNETs can be classified as functional or nonfunctional (non-secreting) on the basis of their secretory hormonal characteristics and the associated clinical picture. The synthesis of several peptide hormones, such as insulin, glucagon, gastrin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and somatostatin, forms the foundation for tumor functionality.

A PNET is labeled as “functional” if it secretes one of these hormones and the patient exhibits the corresponding clinical signs. When a PNET does not release hormones, it is considered “non-functional” (“NF-PNETS”) [7].

Even though they are much more common (around 70%), nonfunctional PNETs (NF-PNETs; also called PPomas) can secrete a variety of peptides, including chromogranin A (CgA), calcitonin, ghrelin, neurotensin, motilin, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), pancreatic polypeptide (PP, in 50–70%), and subunits of human chorionic gonadotrophin (alpha or beta subunits). Nevertheless, these peptides are not associated with a clinically noticeable syndrome [8].

Inadvertent discovery of NF-PNETs usually occurs occasionally, or it can be brought about by tumor metastases, invasion of surrounding structures, or symptoms associated with tumor progression (such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, extreme weakness, and abdominal pain) [9].

Due to a particular hormonal hypersecretion, functional PNETs (F-PNETs), which are uncommon, can cause a variety of sometimes perplexing clinical syndromes; insulinomas are the most common, followed in decreasing order by gastrinomas, glucagonomas, VIPomas, somatostatinomas, PNETs causing carcinoid syndrome, and other rare PNETs [10, 11].

When an NF-PNET manifests symptoms, the most prevalent ones are anorexia and nausea (45%), weight loss (20–35%), and abdominal pain (35–78%). Obstructive jaundice (17–40%), intra-abdominal hemorrhage (4–20%), and palpable masses (7–40%) are less common symptoms.

Metastatic disease may also be the cause of the symptoms (bone pain, lymphadenopathy, brain or pituitary metastases, and so on). According to several published findings, 32–73% of cases have metastases at the time of diagnosis [12, 13].

Histopathological features are used to classify neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that arise at various sites within the body, including PNETs. This classification is crucial because the tumors’ pathological features are roughly reflected in their clinical manifestation: while a small percentage of PNETs exhibit highly aggressive behavior, metastasizing early and posing a threat to life, the majority of PNETs have an indolent course of disease and are typically well-differentiated tumors that behave clinically more like small-cell carcinoma [14].

Parathyroid-hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) has been shown in earlier studies to be secreted by PNETs, although its secretion by gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) is very rare [7].

PNETs that cause hypercalcemia (PTHrPoma, or parathyroid-hormone-related peptide-secreting PNETs) are rare (< 0.1%) and usually originate in the pancreas, and more than 85% of them are malignant [15].

PTHrP is a hormone that causes hypercalcemia of malignancy, most commonly in a variety of solid tumors, including head and neck, lung, breast, and renal cell carcinomas [16,17,18,19]. PTHrP expression in solid tumors with or without hypercalcemia is also linked to metastatic progression and shorter survival in breast and pancreatic tumors [20, 21].

About 20–30% of patients with advanced cancer—both those with solid tumors and those with hematologic malignancies—may develop malignant hypercalcemia. The most frequent cause of hypercalcemia linked to neuroendocrine tumors has been identified as the release of parathyroid-hormone-related protein (PTHrP). Malignant hypercalcemia is accompanied by hypophosphatemia and disproportionately low (suppressed) parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. The diagnosis is confirmed by the demonstration of elevated serum PTHrP levels [22,23,24].

The treatment of hypercalcemia in this context can be challenging [25, 26].

Herein, we present a case of refractory PTHrP-mediated hypercalcemia associated with metastatic PNET.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old Canadian white man was found to have severe hypercalcemia (Table 1) refractory to aggressive hydration, intravenous zoledronic acid 4 mg, and intravenous pamidronate 180 mg.

CT scan of the abdomen revealed a 12.4 × 7.1 × 8.6 cm pancreatic lesion and multiple hepatic metastases.

A liver biopsy confirmed metastatic PNET, which stained positive for CK 19 synaptophysin and chromogranin.

Staining using a monoclonal antibody against the PTHrP N-terminus (PTHrP 1–34 NBP 1 59322 Novus) demonstrated high cytoplasmic expression.

Staining for CXCR4, a chemokine receptor known for its ability to mediate metastasis, was also positive.

PTHrP levels were measured using a two-site immunoradiometric assay (IRMA; Beckman Coulter), in which PTHrP is recognized by an NH2-terminal antibody against PTHrP [1–34] (capture antibody), and a second COOH-terminal antibody against PTHrP [47–86] (signal antibody).

This assay detects a sequence containing the major portion of the first 86 amino acids of the PTHrP molecule but will not detect NH2- or COOH-terminal fragments alone.

Interestingly, PTHrP levels preoperatively were at the upper limit of normal but overlapped with levels seen in normocalcemic cancer patients and healthy volunteers. To firmly establish the underlying mechanism of hypercalcemia, we measured nephrogenous-cycle AMP, a surrogate marker of PTHrP bioactivity, which was very elevated (Table 1). Furthermore, PTHrP levels decreased sharply postoperatively, further supporting the link between tumor expression of PTHrP and its blood levels.

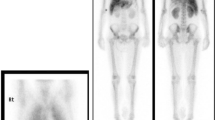

Octreoscan isolated somatostatin avid tissue in the pancreas and liver. Further investigations did not disclose evidence of multiple endocrine neoplasia.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous lanreotide 120 mcg and subcutaneous denosumab 60 mg every 4 weeks and underwent extensive debulking surgery 12 weeks later.

Pathology confirmed a 14.5 cm well-differentiated, intermediate-grade NET with three mitotic figures per 10 HPF, Ki-67 index 10%, and positive cytoplasmic staining for PTHrP (Fig. 1).

It is worth noting that PTHrP staining was weaker in the primary tumor compared with the liver metastasis.

Postoperatively, the patient developed severe hypocalcemia, similar to hungry bone syndrome seen in patients with hyperparathyroidism.

The patient’s hypercalcemia recurred 3 weeks later and was initially refractory to denosumab, lanreotide, everolimus, and hepatic chemoembolization. However, once PTHrP levels normalized, blood calcium levels later normalized following repeated administration of lanreotide and denosumab.

Investigations

See Table 1.

Discussion

PNETs are a diverse set of tumors with multiple categories based on tumor load, functioning, grade, stage, and histological differentiation. A majority of PNETs are considered non-functional [26, 27].

PNETs that are hormone-secreting (functioning) are divided into different categories on the basis of the main hormone they produce and the clinical syndrome they lead to, such as insulinoma, gastrinoma, VIPoma, glucagonoma, and somatostatinoma.

PNETs may also produce other hormones, such as PTHrP, although PTHrP secretion by gastroenteropancreatic NETs is extremely uncommon and seems to be exclusively associated with metastatic NETs. PNETs that secrete PTHrP have only been previously described in case reports [16, 17].

PTHrP is a polypeptide that has been found to share some similarities with PTH (the first 13 amino acids are almost identical) and is expressed in a wide range of neuroendocrine cells. This homology allows PTHrP to function at the PTH-1 receptor site and mimic activities such as increasing bone resorption and distal tubular calcium reabsorption [8, 18]. However, the increased intestinal absorption of calcium does not occur with PTHrP, because it is less likely to stimulate 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production [26].

Malignant tumors of the lung, breast, kidney, and head and neck are more frequently associated with PTHrP-induced hypercalcemia than PNETs [22]). PTHrP in PNETs can also mediate malignancy-related hypercalcemia, which is still incredibly rare and often denotes a poor prognosis [28, 29].

Men and women are equally represented in the demography of PTHrP-secreting PNETs, which is consistent with the overall epidemiology of PNETs. Although there was a large range in age, the majority of patients who presented with it were between the ages of 40 and 60 years [30].

Although a small minority of patients in the published case series had hypercalcemia upon presentation, the majority of patients experienced the onset of symptomatic hypercalcemia between months and years after receiving a PNETs diagnosis [31, 32].

Most patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy and PNETs had metastatic disease, with the liver being the most frequently affected location. In most cases, the patients exhibited hypercalcemia symptoms whether or not they had already been given a PNETs diagnosis. The most often reported symptoms were those associated with hypercalcemia, such as abdominal pain, low appetite, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and weight loss [27].

The management of NET-associated humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy can be challenging, and often requires multimodal treatment.

The acute management of hypercalcemia and the cytoreduction of the tumors should be the two main focuses of the therapy.

Surgical debulking is the most efficient treatment for PTHrP-induced hypercalcemia brought on by PNETs, while many patients might not be suitable [27]. Aggressive tumor cytoreduction with surgery, arterial chemoembolization and/or peptide receptor radionuclide therapy is frequently used in addition to systemic treatment [27, 31,32,33,34].

Somatostatin analogues (SSAs), everolimus, sunitinib, and streptozocin are all agents approved for the treatment of PNETs [14]. In randomized phase III trials, SSAs were linked to symptom management in as many as 70% of patients and a biochemical response in between 30% and 40% of individuals [35].

According to published case studies, SSAs normalize serum calcium levels in patients with PTHrP-induced hypercalcemia; in contrast, in our case report, SSAs did not normalize serum calcium levels for our patient [32].

In addition, chemotherapy with temozolomide and capecitabine (TC regimen) has shown promising results, though its use has only been reported in a few case reports. The response rate to the TC regimen was 39.7%, and both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) improved [36].

There is inadequate evidence to support the effectiveness of other therapies, such as peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), which can be utilized to regulate hormone secretion in PTHrP-induced hypercalcemia [37].

A 58-year-old male patient with nonspecific abdominal pain was described by Kanakis et al. [15] as having significant hypercalcemia as a result of a well-differentiated PNET with widespread liver metastases. Increased ionized calcium levels, low serum PTH, and noticeably high PTHrP concentrations were indicative of PTHrP-related hypercalcemia, which was unresponsive to supportive treatment and several chemotherapy regimens. It took the application of cytoreductive procedures and the development of several molecular-targeted medications to achieve partial control of the humoral condition. Brown tumors, a sign of bone disease, appeared as a result of PTHrP’s continued activity.

The added interest of our case is the finding of PTHrP values at the upper limit of normal despite extreme hypercalcemia and a PTH-like biochemical profile including suppressed PTH, low phosphate, and high nephrogenous cyclic AMP levels, a surrogate marker of PTHrP bioactivity.

This indicates that the circulating PTHrP levels as measured by the two-site IRMA specific for PTHrP (1–86) does not correlate well with the degree of hypercalcemia. When PTHrP levels are not frankly elevated, one needs to ensure that the blood collection was done properly so as to prevent degradation of the molecule (sample collected on ice preferably with a protease inhibitor and quickly centrifuged).

PTHrP measurements should be repeated and, if in doubt, followed by PTH-like bioassay measurements. Newer, more specific and sensitive immunoassays for PTHrP have recently been developed with greatly improved diagnostic performance that could be of great value in monitoring cancer patients [38, 39]

In addition, the findings of positive CK19 staining in the liver and stronger PTHrP/CXCR4 staining in the metastatic lesions compared with the primary tumor may be harbingers of poor prognosis.

Conclusions

We report a case of refractory PTHrP-mediated hypercalcemia in the context of metastatic PNET. Refractory hypercalcemia resolved following PTHrP normalization.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in all the refernces, figure and table.

References

O’Grady HL, Conlon KC. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(3):324–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2007.07.209.

Metz DC, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1469–92.

Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–72.

Caldarella A, Crocetti E, Paci E. Distribution, incidence, and prognosis in neuroendocrine tumors: a population-based study from a cancer registry. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:759–63.

Hruban RH, Takaori K, Canto M, Fishman EK, Campbell K, Brune K, et al. Clinical importance of precursor lesions in the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:255–63.

Marchegiani G, Crippa S, Malleo G, Partelli S, Capelli P, Pederzoli P, et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic tumors in childhood and adolescence: uncommon neoplasms with favorable outcome. Pancreatology. 2011;11:383–9.

Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Mazeh H, Gross DJ. Clinical features of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sci. 2015;22(8):578–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.226.

Ito T, Igarashi H, Jensen RT. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: clinical features, diagnosis and medical treatment: advances. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:737–53.

Eriksson B, Oberg K, Skogseid B. Neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors. Clinical findings in a prospective study of 84 patients. Acta Oncol. 1989;28:373–7.

Oberg K. Pancreatic endocrine tumors. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:594–618.

Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, de Herder WW, Goldsmith SJ, Klimstra DS, et al. NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010;39:735–52.

Kloppel G, Rindi G, Perren A, Komminoth P, Klimstra DS. The ENETS and AJCC/UICC TNM classifications of the neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and the pancreas: a statement. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:595–7.

Garcia-Carbonero R, Capdevila J, Crespo-Herrero G, Diaz-Perez JA, Martinez Del Prado MP, Alonso Orduna V, et al. Incidence, patterns of care and prognostic factors for outcome of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs): results from the National Cancer Registry of Spain (RGETNE). Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1794–803.

Madura JA, Cummings OW, Wiebke EA, Broadie TA, Goulet RL Jr, Howard TJ. Nonfunctioning islet cell tumors of the pancreas: a difficult diagnosis but one worth the effort. Am Surg. 1997;63:573–7; discussion 577-578.

Kanakis G, Kaltsas G, Granberg D, Grimelius L, Papaioannou D, Tsolakis AV, et al. Unusual complication of a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor presenting with malignant hypercalcemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E627–31.

Rizzoli R, Sappino AP, Bonjour JP. Parathyroid hormone-related protein and hypercalcemia in pancreatic neuro-endocrine tumors. Int J Cancer. 1990;46(3):394–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910460311.

Shirai K, Inoue I, Kato J, Maeda H, Moribata K, Shingaki N, et al. A case of a giant glucagonoma with parathyroid hormone-related peptide secretion showing an inconsistent postsurgical endocrine status. Internal Med. 2011;50(1):1689–894. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5357.

Kremer R, Goltzman D. Parathyroid hormone related peptide (PTHrP) and other mediators of skeletal manifestations of malignancy. In: Bilezikian JP, Martin TJ, Clemens TL, Clifford CJ, editors. Principle of bone biology. eBook ISBN: 9780128148426.

Truong NY, deB Edwardes M, Papavasiliou V, Goltzman D, Kremer R. Parathyroid hormone related peptide and survival of patients with cancer and hypercalcemia. Am J Med. 2003;115(2):115–21.

Assaker G, Camirand A, Abdulkarim B, Omeroglu A, Deschenes J, Joseph K, Noman ASM, Ramana Kumar AV, Kremer R, Sabri S. PTHrP, a biomarker for CNS metastasis and node-negative adjuvant chemotherapy-selection in triple-negative breast cancer). J Natl Cancer Inst Cancer Spectrum. 2020;4(1):063.

Pitarresi JR, Norgard RJ, Chiarella AM, Suzuki K, Bakir B, Sahu V, Li J, Zhao J, Marchand B, Wengyn MD, Hsieh A, Kim IK, Zhang A, Sellin K, Lee V, Takano S, Miyahara Y, Ohtsuka M, Maitra A, Notta F, Kremer R, Stanger BZ, Rustgi AK. PTHrP drives pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis and reveals a new therapeutic vulnerability. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(7):1774–91. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-20-1098.

DeLellis RA, Xia L. Paraneoplastic endocrine syndromes: a review. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:303–17.

Kaltsas G, Androulakis II, de Herder WW, Grossman AB. Paraneoplastic syndromes secondary to neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R173–93.

Grunbaum A, Kremer R. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) and malignancy. In: Litwack G, editor. Parathyroid hormone (the “Volume”). Vitamins and hormones. Elsevier Inc. San Diego, CA; 2022.

Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1727–33.

Zhu V, de Las MA, Janicek M, Hartshorn K. Hypercalcemia from metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor secreting 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5(4):E84–7. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.042.

Pitts S, Mahipal A, Bajor D, Mohamed A. Hypercalcemia of malignancy caused by parathyroid hormone-related peptide-secreting pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PTHrP-PNETs): case report. Front Oncol. 2023;12(13):1197288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1197288.

Clemens P, Gregor M, Lamberts R. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with extensive vascularisation and parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP)-associated hypercalcemia of malignancy. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001;109(07):378–85. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-17411.

Ralston SH, Gallacher SJ, Patel U, Campbell J, Boyle IT. Cancer-associated hypercalcemia: morbidity and mortality. Clinical experience in 126 treated patients. Ann Internal Med. 1990;112(7):499–504. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-112-7-499.

Wu TJ, Lin CL, Taylor RL, Kvols LK, Kao PC. Increased parathyroid hormone-related peptide in patients with hypercalcemia associated with islet cell carcinoma. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1997;72(12):1111–5. https://doi.org/10.4065/72.12.1111.

Milanesi A, Yu R, Wolin EM. Humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy caused by parathyroid hormone-related peptide-secreting neuroendocrine tumors: report of six cases. Pancreatology. 2013;13(3):324–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2013.02.007.

Kamp K, Feelders RA, van Adrichem RCS, de Rijke YB, van Nederveen FH, Kwekkeboom DJ, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) secretion by gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs): clinical features, diagnosis, management, and follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(9):3060–9. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1315.

Papazachariou IM, Virlos IT, Williamson RCN. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours associated with hypercalcaemia. HPB (Oxford). 2001;3(3):221–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/136518201753242253.

Igarashi H, Hijioka M, Lee L, Ito T. Biotherapy of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors using somatostatin analogs. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sci. 2015;22(8):618–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.227.

Caplin ME, Pavel M, Ćwikła JB, Phan AT, Raderer M, Sedláčková E, et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):224–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1316158.

Ramirez RA, Beyer DT, Chauhan A, Boudreaux JP, Wang YZ, Woltering EA. The role of capecitabine/temozolomide in metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncol. 2016;21(6):671–5. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0470.

Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, Hendifar A, Yao J, Chasen B, et al. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):125–35. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1607427.

Otieno BA, Krause CE, Jones AL, Kremer RB, Rusling JF. Cancer diagnostics via ultrasensitive multiplexed detection of parathyroid hormone-related peptides with a microfluidic immunoarray. Anal Chem. 2016;88(18):9269–75.

Dhanapala L, Joseph S, Jones AL, Moghaddam S, Lee N, Kremer RB, Rusling JF. Immunoarray measurements of parathyroid hormone-related peptides combined with other biomarkers to diagnose aggressive prostate cancer. Anal Chem. 2022;94(37):12788–97. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.2c02648.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the patient, and the laboratory team at the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, McGill University Health Center.

Funding

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant #MOP 142287.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH contributed to validation of data and writing the original draft and review and editing the article; JWY contributed to data curation and formal analysis, investigation, and methodology steps; RK contributed to project administration and resources management, funding acquisition, methodology building, formal analysis, and the reviewing of the original draft of article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haimi, M., Yang, J.W. & Kremer, R. Refractory hypercalcemia caused by parathyroid-hormone-related peptide secretion from a metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: a case report. J Med Case Reports 19, 54 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-025-05074-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-025-05074-9